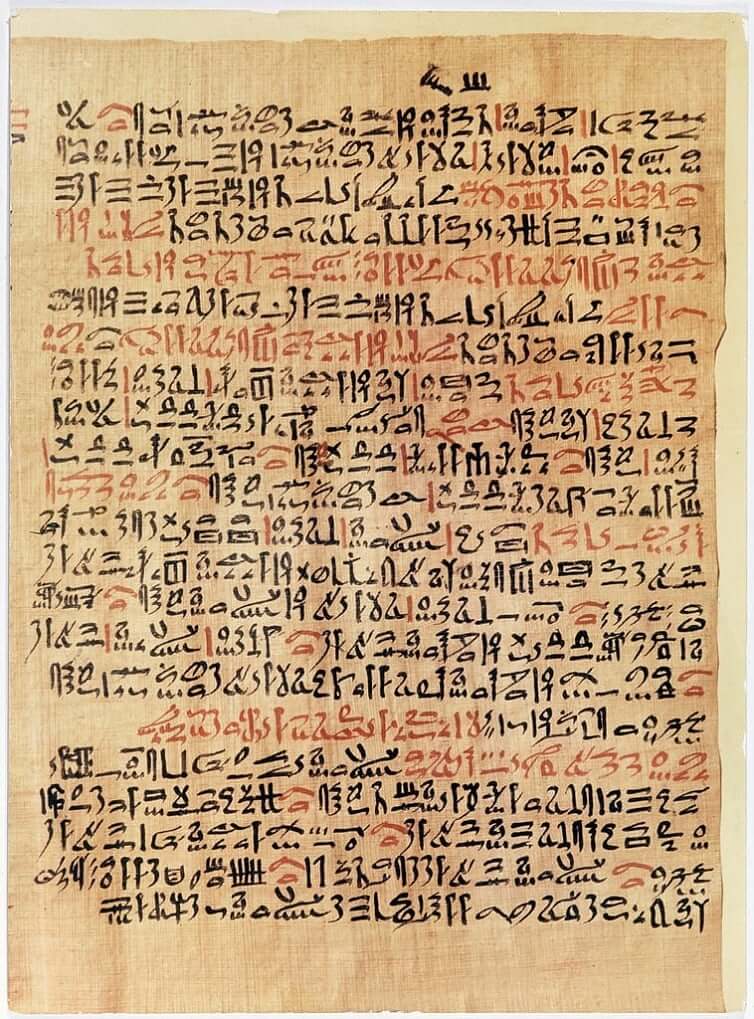

Clinical documentation has a deep pedigree that dates back more than 4000 years to the ancient Egyptians. Transcribed onto papyrus in a format surprisingly similar to modern day case presentations, clinical documentation appeared to have served the dual purpose of teaching apprentices and guiding the management of future patients. Subsequently, Greek physicians continued this practice of medical recordkeeping, but built on its content by introducing the notion of disease dynamics. They recognized that diseases have typical and natural trajectories. They not only documented the evolution of diseases, but also the impact of their interventions to alter that trajectory. This methodology of observation, intervention, and documentation was thereafter augmented and transmitted by the Arabs, and arrived to Europe where it was incorporated into the larger cultural projects of enlightenment and statism.

The next development in medical recordkeeping occurred in the mid-20th century as part of the larger transformation of medicine from an art to science-based endeavor. The physician informaticist Dr. Lawrence Weed envisioned clinical documentation as analogous to a scientist’s laboratory notebook. He emphasized reliable data collection, clarity, thoroughness, and organization. He designed a standardized template for documentation called the S.O.A.P (Subjective, Objective, Assessment, Plan) note and developed the problem oriented medical record (POMR). One of his key insights was that a medical note was not only useful for recordkeeping and communication, but also that the act of creating a note, by breaking down the patient presentation into system based problems, would serve as a cognitive scaffold for the physician creating the note. In his vision, note creation was an integral part of patient care.

Dr. Weed championed the development of the digitized, electronic medical record (EMR) and believed they would accelerate his project for clinical documentation. In fact the S.O.A.P note and the problem lists are ingrained in the practice of medical documentation and the US healthcare has completely transitioned to an electronic health record (EHR). However, much of his vision has been unrealized. Physician documentation is neither akin to a scientist’s laboratory notebook, nor is the process of documentation considered to be an intellectual, cognition-boosting creative endeavor. As digitized records have become ubiquitous, medical note creation has (d)evolved into a task that mostly serves bureaucratic, administrative, legal, and economic goals. Physicians now come to associate the task of documentation with such dread and disdain that it is considered a leading factor in the epidemic of physician burnout.

In response to the discontentment, a cottage industry has blossomed to alleviate the “burden” of documentation. There has been a proliferation of best practices and EHR-based tools such as reason for visit templates and dot phrases. Documentation of the review of systems and physical exams entails a series of clicks – or even more efficiently a single templated click. Copying sections of prior notes and pasting them into the current note is notoriously prevalent. Medical documentation is laden with boilerplate language and codes designed to optimize billing, mitigate risk, and satisfy metrics. It would not be an exaggeration to claim that the majority of a medical note is now constructed via these time-optimizing tools. Thus in aggregate, the corpus of documentation is not only generic, depersonalized, and lacking the patient perspective, but also riddled with errors.

The loss of personalization in documentation has followed larger shifts in medicine that increasingly devalues the subjective. The homogenizing tendencies of population health (future essay), the assembly line-like delivery of healthcare (future essay), the rush to anoint medicine as a determined and information-based science (future essay) has dehumanized, depersonalized, and objectified the individual patient. Reducing them to buckets of biomarker values, imaging results, and diagnoses. Unsurprisingly, clinical documentation has reflected this shift in values. Whereas, diagnosis codes, laboratory values, and imaging results have ascended in importance, the “S” (subjective) of the SOAP note and the subjective parts of the “O” – review of systems and physical exam – have essentially been sacrificed to the altar of efficiency. The intersubjective aspects of patient care – shared decision making, consent discussions – are reduced to legalese and dot phrases. This loss of contextual information has downstream consequences (next essay). The “S” not only carries important, meaningful, and salient information relevant for secondary use, but the subjective and the intersubjective – the patient-physician relationship – is the humanizing, care-based aspect of medicine and important for primary use and patient outcomes (next essay).

Despite the circuitous four thousand year journey, for much of history, medical recordkeeping has primarily been a tool for physician training and patient care. In the 21st century, by scaling and institutionalizing digitized healthcare data, it was anticipated that by making data amenable for analysis, patient care would be revolutionized. However, this outcome has mostly not (yet) been realized (upcoming essay). What has been realized is that medical recordkeeping has transitioned into a tool that mainly serves administrative, economic, and legal functions. Although it carries value as a tool for patient care, the task of documentation is no longer perceived as a creative or scaffolding endeavor for the physician. Furthermore, following the broader shift in medicine that (over)values the “objective” and minimizes the importance of the “subjective,” it is the “S” – the patient perspective – that has become increasingly less represented in clinical documentation. Thus, although digitized medical records given the veneer of thick descriptions, they are in fact thin and lossy (next essay).

Discover more from S-Fxn

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] for qualitative social science research. Although not typical viewed through this framework, a S.O.A.P themed note is a combination of thick and thin descriptions that includes facts, interpretations, […]