It has proved to be a difficult endeavor to pin-down specific human universals. Exceptions appear to be the rule. Nonetheless, although the specifics vary, in broad terms it can safely be claimed that humans are universally social, symbolic, and ritualistic. Humans across time and space have and continue to be bound in webs of relationships that are suffused by symbols and rituals that engender belief, expectation, and bonds. From this perspective, it becomes obvious that relationships are key factors for well-being and health. One relationship that holds special value with surprisingly deep roots is the physician-patient relationship. Its origins can be sourced to the grooming practices of our primate ancestors nearly 10 million years ago, and traced through the shamanistic practices that span at least 30,000 years.

Chimpanzees are known to be zealous groomers. They devote a significant amount of time grooming and being groomed. Their grooming practices include removing dirt, plants, dried skin, and bugs. The groomer is frequently observed parting the groomee’s hair in a repetitive, massage-like motion. These practices are believed to have two purposes. First, they serve to directly promote health. The act of grooming not only removes disease conferring parasites , but is shown to be physiologically relaxing. Second, these practices are a form of politicking. They facilitate bonding, allow for alliances, and generally enable individual chimpanzees to navigate troop hierarchy. It is an example of reciprocal altruism that is also present in human interactions and denoted by phrases such as “you scratch my back and I’ll scratch yours.”

With the expansion of the neocortex in the human lineage, reciprocal altruism not only increased in scale but also diversified in types. The expansion of the prefrontal cortex coevolved with an increase in the capacity for intersubjectivity – sharing the emotional state of another and adopting their perspective. This not only allowed an increase in the scale of relations, but also enabled relationships to become more specialized. Built on this foundation of intersubjectivity, reciprocally altruistic grooming practices became the building blocks for caring for the weak, the sick, and the elderly in human societies. Thereafter, as individuals in human societies took on specialized roles, the role of the groomer converged onto the most empathic, altruistic, and charismatic member of the society – the shaman.

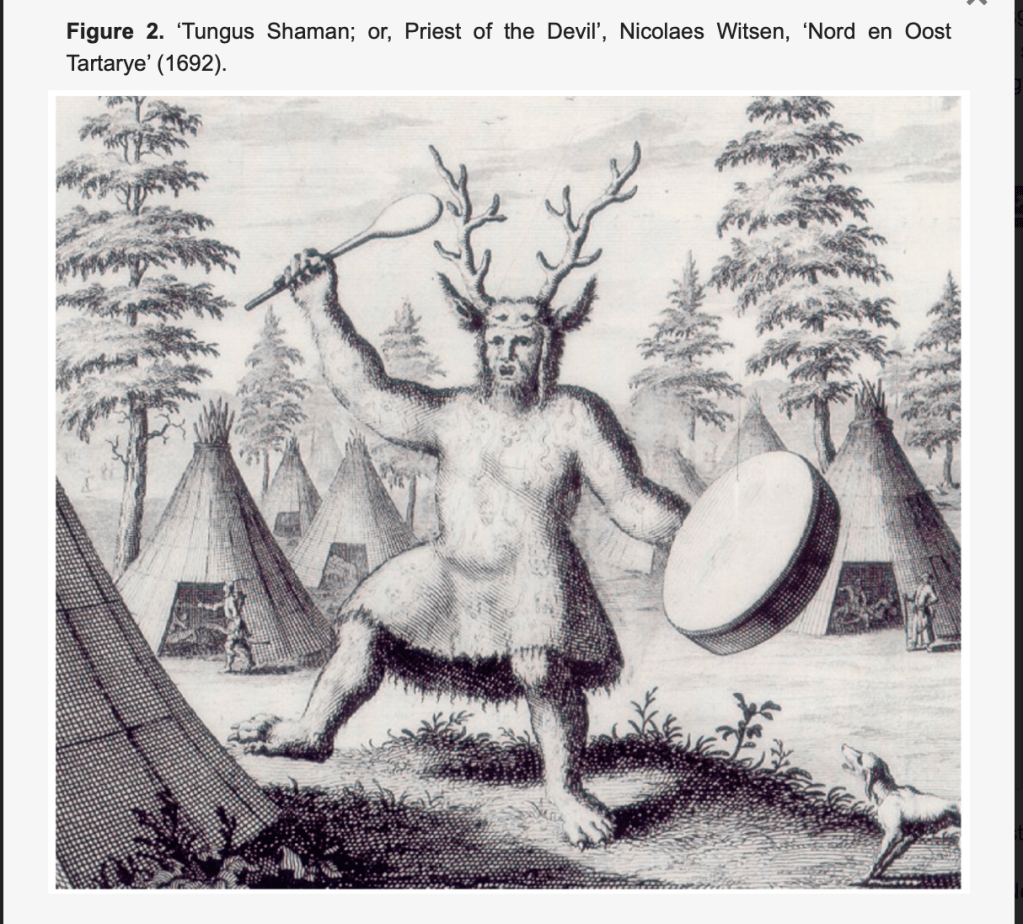

Shamanism, a term derived from the Tungus people of Siberia, represented the first human example of medical care. There is evidence of shamanistic practices that date 30,000 years in the form of cave painting, rock art, and artifacts. The figure of the shaman is central to shamanism. The shaman was a priestly figure who was thought to possess special powers of healing, divination, and communication with the spirit world. She developed these skills through a rigorous training and apprentice program. He learned to use herbal medicines, trained in channeling spirits, led ceremonies, and manipulated the body to treat “soul loss,” alleviate suffering, and promote healing. Rituals, expectation, and belief suffused the shamanstic experience. Ancient Mesoptamian, Indian, Egyptian, Chinese, and Greek civilizations built on these shamanistic practices and developed their individualized methodologies and philosophies for healing.

Allopathic medicine emerged out of the Greek tradition and made the scientific turn during the enlightenment. In adopting “objective-scientific” stance, medicine has achieved tremendous successes in diagnoses and treatment. In parallel, healthcare has made remarkable gains in efficiency by adopting “industrial-capitalist” (future essay) practices. Despite these successes, the gaps in knowledge and legibility into disease processes remain chasmic (future essay). Treatments are non-specific (future essay). Evidence of their effectiveness remains sparse. Especially because of these factors, medicine and healthcare must attend to personalization, empathy, and care. Consideration of subjectivity, recognizing the importance of the physician figure, creating environments that foster the patient-physician relationship, maintaining rituals that engender belief are paramount because they can directly advance or impede healing (next essay).

Reading

Discover more from S-Fxn

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.